That wildlife constitutes less than 4 percent of all land mammals!

E for Elephant? Wrong.

E for Egg. E for Emu. E for Emma the bot? Right.

No joke, that. Children of the next generation may well not know an elephant as well as a bot or some variety of poultry. On World Wildlife Day, a sobering thought is that wild animals comprise less than 4 percent of mammals while humans and livestock add up to the remaining 96 percent (with 60 percent of this being livestock). The planet has been re-engineered by humans to cater to their needs that include farming, meat production and development. Welcome to the Anthropocene.

The study published last year by scientists at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science, calculated the total biomass on the planet using data and computation to conclude that wild land mammals alive today have a total mass of 22m tonnes. By comparison, humanity sits heavy at around 390m tonnes and livestock heaviest at 630 m tonnes!

The biomass of pigs alone is nearly double that of all wild land mammals.

Two years ago, the team had estimated around 50m tonnes of wild mammals and the latest calibration shows the picture to be much more distressing.

Human explosion

In just 200 years human population has rocketed from 1 billion to 8 billion! While advancements in medicine helped stem mortality, using technology, the race has altered the landscape of the planet to suit its demands while destroying habitats of many species. The Anthropocene or the era of the humans influencing the ecosystem is presently on way to see the sixth mass extinction of species. Wildlife is well ahead in the line.

Does anyone care? And if we do, what can be done? Especially given that human population will not see any immediate drop in the climb, nor the livestock numbers that cater to a burgeoning demand for meat.

We must ensure that the miniscule 4 percent of land that constitutes protected areas in a country like India is not further eaten into, in the name of development projects, highways or railway lines, or farm encroachments.

We must improve the protection for wildlife within protected areas, which should include habitat preservation and improved patrolling. This would call for ramping up the numbers in the forest department which continues to be understaffed and poorly equipped. This again calls for prioritisation of forests and their protection.

But, given the recent amendment to the Forest Conservation Act, clearly the rulers seem more focussed on ‘development projects’ than protection of forests. The modifications to the 1980 Act allow for not only diversion of forests for projects linked to national security (almost 90 pc of Nagaland, chunks of Assam, and whole of Meghalaya, Tripura and Assam), but also exempting several eco-tourism activities from the purview of the Act.

From the landmark 1996 Godavarman case filed in the Supreme Court, the definition of forest was to be that of any land recorded under any law as forests in the government records and satisfying the dictionary definition. The latest amendment has allowed for a dilution of the definition of forests, making it convenient to alter almost 28 percent of forests that lie outside the records. Many of these are home to endemic species which will have no protection henceforth.

We must spread awareness and sensitivity to the protection of wildlife and forests among the citizens. Besides the noble intention of being a steward for all life on the planet, we cannot forget that these shrinking patches of green with its rich biodiversity sustain many rivers and act as major carbon sinks on land. Wildlife plays a crucial role in keeping the forest ecosystem balanced and healthy.

“However, besides playing crucial role in our own survival, we must protect wildlife as they are part of this world and have every right to their place on earth,” says D V Girish, wildlife conservationist who has played a pivotal role in the voluntary resettlement of over 450 families from the Bhadra tiger reserve. Winner of many awards, both national and international, he continues to inspire and lead young volunteers in being the voice of the wilderness, especially in the Chikmagalur ecosystem.

But as human population rises and makes more demands on these last surviving preserves, wildlife is bound to be the loser.

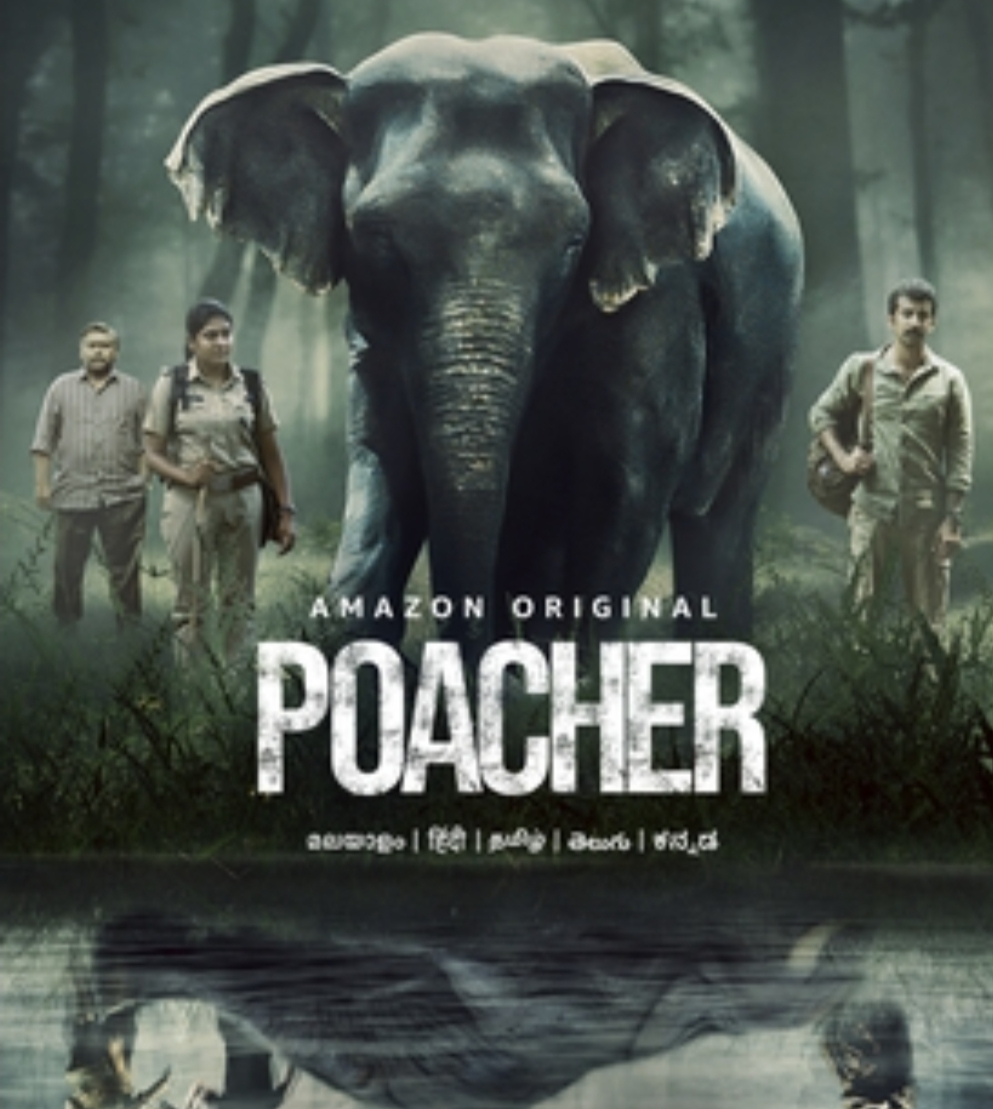

The highly acclaimed series ‘Poacher’ being streamed on Amazon Prime calls attention to some of the challenges. Based on the country’s largest ivory seized from poachers during the 2015-2017 Operation Shikar in Kerala, it points to the wildlife trade link to the terrorist groups and drug mafia. The helplessness of the officers and the authorities in pursuing or arresting the influential buyers in the list on hand tells it all. There can be no end to it. Small players will come and go, leaving the place for others to follow.

The investigation revealed the poaching of over 18 tuskers (or more) in the many ranges of Vazhachal and Athirapalli forests in Kerala. The forest department was caught napping, complacent in the confidence that poaching was a thing of the past, after a wide elephant poaching ring was burst in 1994. It is a reminder that vigilance cannot be relaxed.

After the arrest of 73 people and recovery of ivory worth Rs 25 crore, the 19 cases initiated by the KFD are still in court! Though the case was handed over to the CBI over inter-state and international involvement, there was nothing more uncovered.

Lack of patrolling, heavily understaffed and poorly equipped forest department, apathy and corruption, have been cited often as the problems facing wildlife protection. The series gives a good snapshot of the above.

Finally, the killing will stop only when the buying does. “Poaching is always a threat. One must never be complacent. The trader and poacher should be arrested. The consumers should first be made aware and then of course legal options should also be looked at,” says Vivek Menon, founder and Executive Director of WTI, presently also serving as Deputy Chair of IUCN-SSC and Chair – Asian Elephant Specialist Group.

‘Poacher’ shows what a handful of committed persons can do as opposed to the lazy apathy that rules a majority. It is the same question that will be voiced by many as posed by a friend of one hunter – why are you making a big thing out of the killings of a few elephants??

To many eking out a livelihood, the lure of some fast money can be tempting. They will not bat an eye to the dying cries of an elephant shot in the head. Instead, they will most likely ask, like the guy does in the series, what about the crops destroyed by the elephants. What about the mouths to feed at home?

It brings us back to the problem of a gargantuan human population that lays siege to more and more land, leaving nothing much for wildlife. The forests are depleted of nutrients that the animals need, thanks to human intrusion. When elephants migrate based on the routes handed down generations in their DNA, they encounter paddy and ragi fields. Here is much needed nutrition that is tasty too. The gentle giant will ask for more. And be punished.

Deceased Thaneer before he became ‘wanted’. (Pictures and video courtesy RFO Shilpa)

It was a similar fate that befell Thaneer from Hassan. One day he was helping himself to some delicious jackfruits that elephants love. (Watch the video) Seeing him near the estates triggered the panic in humans, though he had never harmed anyone. He was tranquilised and moved to Bandipur from where he moved to Mananthavady in Wayanad and raised a panic, not because he harmed anyone, but simply because he went strolling down the streets. He was tranquilised several times before capture and died on reaching Bandipur from suspected overdose.

“Though he strayed into coffee estates he never harmed any human. Personally I liked him because he was friendly,” says range officer Shilpa who had seen Thaneer often on her beat around Belur.

Wayanad is a typical example of a human-elephant conflict zone with burgeoning human population in and around the forests. It is also a classic example of habitat destruction with 62 percent forest cover lost between 1950-2018 and a boom in plantations by 1800 percent!

Experts have often noted that the depleting quality of the forests with foreign invasive species low in nutrition often leads to the larger wildlife straying out of the forests in search of food. Relocating animals has not been successful as the animal manages to return to its territory. This has seen with tigers, leopards and elephants too. They too have homes.

Do we care if they survive or not? Anyone who has seen an elephant or tiger, a squirrel or macaque, a gaur or sambar, in the wild, cannot but be spell bound by that moment, forever. In them you may see what we have lost. Besides questions on whether they are sentient, and what role they play in the web of life, can we just let them be, because the planet is their home too.

By Jaya