Joint management of protected areas with communities living on and around the region should be the approach if we are to hold on to a fast vanishing wildlife. Not unregulated wildlife tourism that caters to adrenalin rushes for a few folks and moolah for others.

Today our protected areas are little under 5 pc of the geographical area. Globally wildlife comprises around 6 pc of the biomass of all land mammals as calculated in a study. Human population and that of livestock bred for meat and dairy is eating into wild habitats. How do we save the last of the few remaining wildlife? Is it by strict protection of habitats or by creating public awareness on the issue?

If it is through garnering public support, does it have to be necessarily through wildlife tourism? Is that the best way to forge a connection for the millions who live totally cut off from the wilderness? Do we need to ‘see’ to believe the need for conservation? We have learnt to accept the invisible electron without demanding to be shown one. Can we not similarly accept the imperatives of conservation from what the experts say? Can we not achieve the same results through education?

Cornered! by tourist vehicles

Cornered! by tourist vehicles

It is a mixed verdict. Barring a few wildlife activists who think the best way to protect wildlife and the wilderness is to cordon off these areas with minimum to nil human presence, most of the opinion veers towards an approach that involves the local communities and a regulated tourism.

A third choice is wildlife tourism. Tourist operators will convince you on the need to take people close to the animals through safaris and other packages. An elephant will remain a distant entity to be feared rather than respected or admired, one operator told me. “But if you take people to the forests and they see the animal in its surroundings, and learn about their behaviour and needs, it makes more of an impact.”

Perhaps. But the fact remains that in today’s world of instant gratification, it is a click with a lion or a hippo at dangerously close distances that the average tourist is aiming at. This is evident whether one visits Ranthambore National park in India with jeep loads of tourists invading the tiger’s territory. So also in Africa’s Maasai Mara or Ambroselli park.

Putting up with humans?

Putting up with humans?

Tourist guides and operators succumb to a few extra bucks and drive closer to the animals than allowed, sometimes even allowing tourists to disembark and pose! As observed in an article, the focus is not so much on the animal as it is on building a business brand.

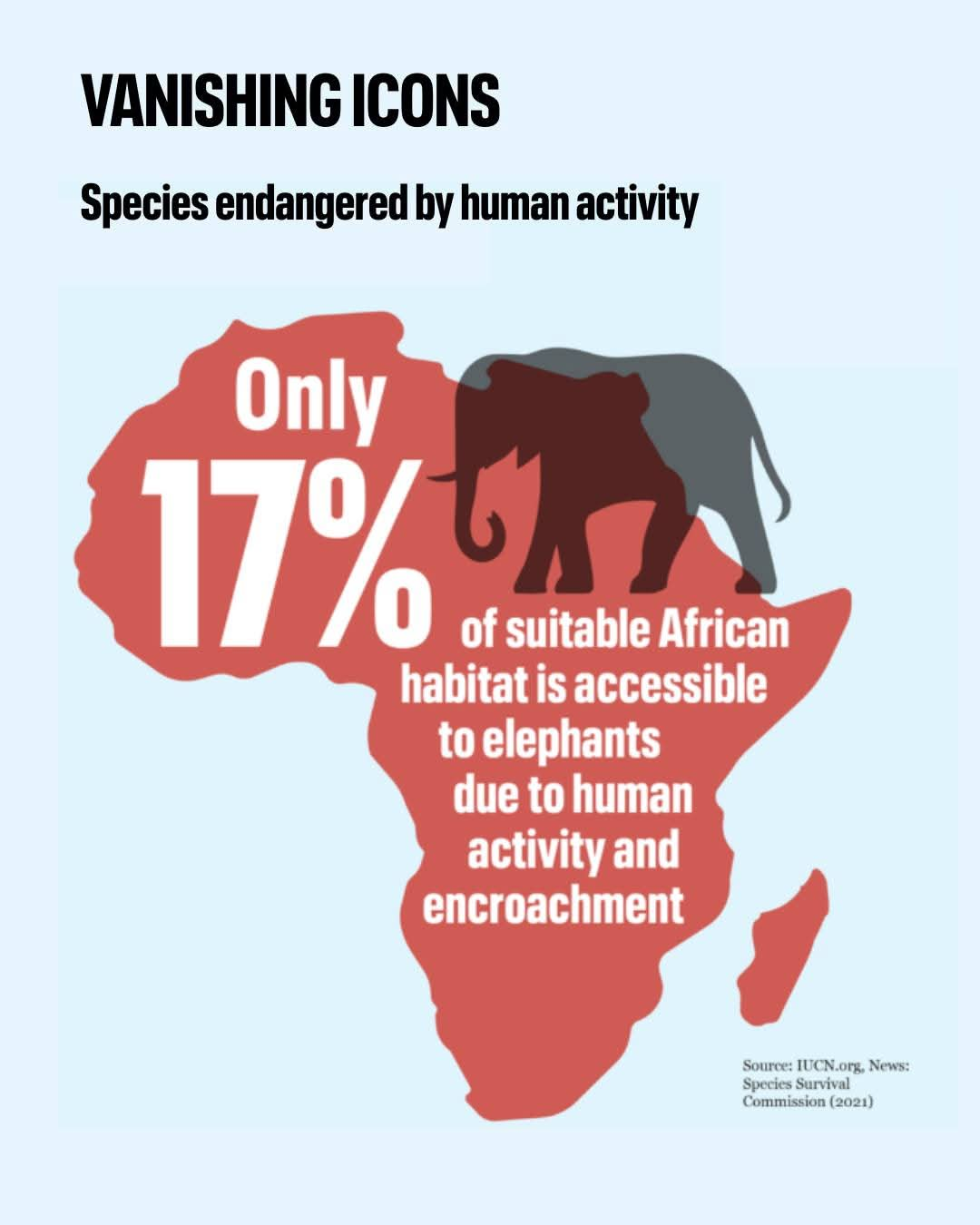

To these tourists intent on posting their daredevilry on the internet, it does not matter that the Asian or African elephant numbers have dropped drastically due to loss of habitat to humans.

Animal crossing, human frenzy

During a recent trip to Africa, I happened to witness how a fear of missing out led to the sad death of a few wildebeest. This was somewhere along the northern Serengeti in Tanzania when the antelope herds undertake the perilous journey across the river Mara many times over in order to gain access to the green grass on the other side. One of the largest natural mammal migrations on the planet today, around a million or more wildebeest move in large groups and cross the river. It was at one such point we witnessed a flurry of human activity with a 100 or more Land Cruisers racing to a crossing point on receiving news of an impending crossing.

African wildlife tourism is pretty costly, beyond the budget of the average middle-class Indian. Even for a European or American, the costs are steep. So, having paid up for the big event, no one wants to miss on the spectacle as hundreds of bleating, mooing, jostling wildebeest plunge into the river and take a life or death chance with the lurking crocodiles. In the rush to reach a vantage point to get the best clicks, the vehicles knocked down two or more wildebeest. Hardly anyone bothered. They had all got their shots.

For the operators, tourism helps keep their coffers flowing. For the tourists, it is an adrenalin rush. To the elephant and the lions or tigers, it is a disturbance that they are putting up with, much better than we humans would to a troop of uninvited visitors trampling through the rooms of our home.

I remember a conversation with the late Papa Wakefield of Kabini Jungle Lodges, where he advocated tourism as a means to also keep a watch for poachers, believing the presence of tourist vehicles would act as a deterrent. But experts everywhere will agree that the keyword is restricted numbers. There are formulas for calculating the carrying capacity of a park or sanctuary but it remains mostly in paper, with new routes being opened up for public as the demand rises.

Power of the narrative

In Ranthambore, we have witnessed the dangers of over populating with tourists when three people recently met their end at the hands of late Arrowhead’s cubs. Being used to seeing so many humans, the tigers lost the fear of them. Also aiding this aggression was the practice of live-baiting to supplement the food for the big cats. But, who is Arrowhead? Grand-daughter of the famous Machli, she shot into the limelight thanks to documentaries and photographs by Valmik Thapar and the tribe of wildlife enthusiasts.

Watching with pride and love over the years, while documenting their lives, these film-makers helped popularise the individual tigers and carve a story around each. Naturally, the people who read and saw the narratives wanted to see it all ‘live’, even if it meant paying around a 1000 Rs for a one-hour drive.

That is then how the narrative of popularising the tigers and endearing them to the humans is backfiring. It is now being criticised for the burden the park bears in terms of burgeoning tourist numbers. This has gone up by 6 lakh in a decade, thanks to easy access from Delhi, Jaipur and other cities. In return, have these popular narratives helped the cause of the tiger? Have we as humans for instance stopped demanding faster roads, knowing that they often cut through wildlife habitat? Not really. Have we stopped encroaching on forest lands or learnt to co-exist? Sadly, no.

The recent poisoning of a tigress and her four cubs at MM Hills in Karnataka points to how human wildlife conflicts are here to stay. Tiger and elephant deaths in Karnataka alone point to a poor conviction rate as also delayed compensation for cattle and human lives lost, besides a poorly equipped and paid forest department staff. Last year saw over 35,000 conflict cases in the state. Data from the unreleased 2022–23 Elephant Census in India indicates the elephant population has decreased by 20% in five years, with the drop steeper in some of the north eastern states.

Revenue spinner

That brings us back to the question of wildlife tourism and the need for it. However much one feels strongly about the need to leave wildlife alone, this is an area that is a booming revenue spinner. Wildlife tourism in India fetched around 11,246 million US dollars in 2023 and this is poised to almost double by 2030! It is here to stay. In the context of rising human wildlife conflict, the bigger question is how this revenue is being used to provide livelihood support for of people living close to these habitats. “Wildlife tourism has to be managed with a focus on reducing carbon footprint, ensuring that tourism doesn’t disturb wildlife, damage environment or negatively impact local communities,” as pointed by wildlife biologist Ravi Chellam. “Tourism ownership and management must include local representatives so they have a say in it.”

A growing tribe of eco-sensitive hoteliers and tour operators are disbursing part of their income by appointing staff from the local community, and tickling the local economy by advertising the local wares and handicraft. Tourists are taken to interact with locals and get a peek into their lifestyle. In the long run, such immersion can win some financial support for the communities. In turn, their dependence on the forests will reduce.

Joint management

In Kenya’s Maasai Mara, the Maasais are partners with conservation experts in managing the Mara Triangle. The Mara Conservancy is a public private partnership that has successfully managed to regulate tourist numbers and get the Maasai people involved in conservation. This has helped bring down the conflicts involving cattle and wildlife.

At the Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala, efforts have been in place since a few decades towards resource conservation and community welfare by drawing the local tribal communities into the eco-tourism venture. Many indigenous tribe members have turned from poaching and other illegal activities into forest protectors. Such inclusive management of protected areas has to be incorporated more extensively if we are to preserve wildlife for posterity. We also need to educate the next generation on the need to be sensitive to the needs of wildlife. Sadly, environment education which was a subject of study has been discontinued for reasons best known to the powers that rule.

6 Reasons Why Wildlife Conservation Should be on your To-Do List | WWF

Wildlife gains nothing from a mindless tourism where camera wielding, noisy crowds get their moment of glory at the cost of disturbing the wildlife and littering the surroundings. Encouraging this will merely go to make a few rich resort owners and tour operators richer.

By Jaya